Introduction

Think of DNS like the Internet’s phone book: it turns names you understand into addresses computers use. In this guide, we’ll walk through four simple views how DNS is built, how it can block threats, common attacks and defenses, and how it fits into a “never trust, always verify” network modelso that even if you’ve never worked with DNS before, you’ll see exactly how to keep it safe.

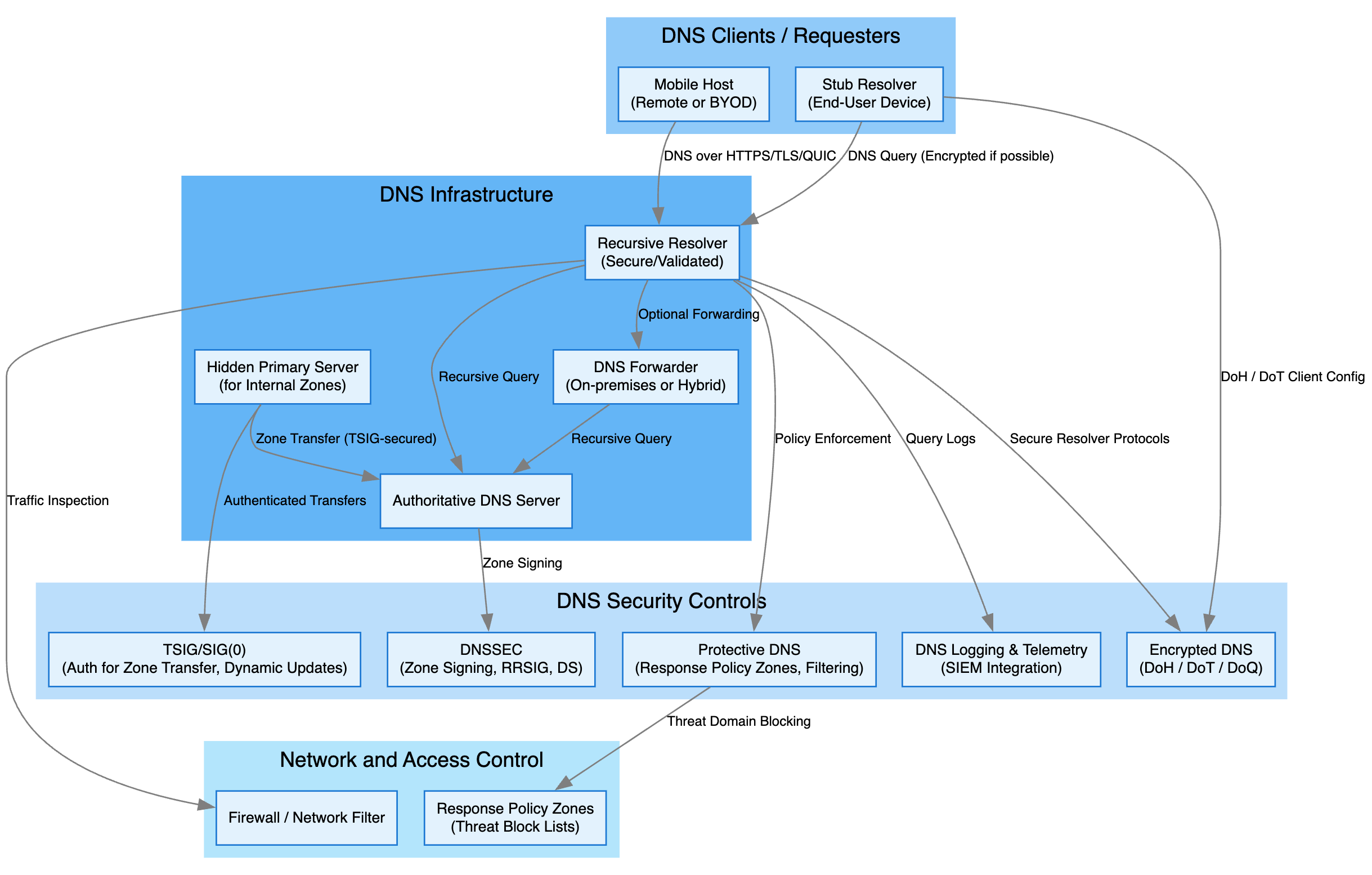

Part 1 – Secure DNS Deployment Architecture

1. Introduction

Domain Name System (DNS) is the “phone book” of the Internet: it translates human-friendly names (e.g. www.example.com) into IP addresses (e.g. 93.184.216.34).

In a secure DNS deployment, we add layers of cryptographic validation, encrypted transport, policy enforcement and logging to protect against tampering, eavesdropping, and abuse.

This section walks through a conceptual architecture map (see diagram) and explains how the pieces fit together, even if you’ve never designed a DNS service before.

2. Core Components

2.1 DNS Clients / Requesters

Stub Resolver (End-User Device)

- Built into every OS (Windows/macOS/Linux) or embedded in IoT devices.

- Sends DNS queries to a recursive resolver typically “just asks” for the IP of a name.

Mobile Host (Remote or BYOD)

- Laptops/phones on the corporate VPN or public Wi-Fi.

- Configured to use encrypted DNS (DoH/DoT/DoQ) back to corporate resolvers.

2.2 DNS Infrastructure

Recursive Resolver (Secure/Validated)

- The workhorse that accepts queries from stubs or mobile hosts.

- Validates DNSSEC signatures when resolving names in signed zones.

- Can be configured to forward unknown queries to a trusted DNS Forwarder.

DNS Forwarder (On-premises or Hybrid)

- Acts as an intermediary centralizing policy enforcement, caching, or forwarding to cloud resolvers.

- Useful for hybrid setups where some traffic stays on-prem while other queries hit a cloud-based DNS security service.

Authoritative DNS Server

- Holds the “ground truth” for your own domains (internal or public).

- Hidden Primary for internal zones: not exposed to the Internet, only to forwarding/mirror servers.

- Secondary servers (mirrors) can be distributed across data centers or cloud regions.

3. Security Controls & Protocols

Underpinning the core DNS components are dedicated security layers:

| Control | Function |

|---|---|

| TSIG / SIG(0) | Authenticates and secures zone-transfer or dynamic update operations between servers. |

| DNSSEC | Cryptographic signing (RRSIG) of DNS records; chain-of-trust via DS records in parent. |

| Encrypted DNS (DoH / DoT / DoQ) | Encrypts the stub↔recursive channel to prevent eavesdropping and on-path tampering. |

| Protective DNS (RPZ) | Response Policy Zones to block or redirect malicious/domains based on threat feeds. |

| DNS Logging & Telemetry | Full query/response logging, metadata export (source IP, timestamp, domain). |

4. Network & Access Control

Firewall / Network Filter

- Enforces which DNS servers and protocols (UDP 53, TCP 53, 853, 443, etc.) are allowed.

- Example: only allow port 853 (DoT) to your recursive resolver from managed endpoints.

Response Policy Zones (Threat Block Lists)

- Implemented at the recursive layer or at the firewall via DNS intercept.

- Drops or “NXDOMAINs” known bad domains before they ever reach a client.

5. Trusted Communication Paths

Stub → Recursive

- Prefer DNS over HTTPS (DoH) or DNS over TLS (DoT) from user devices.

- Fallback to plain UDP/TCP port 53 only on legacy endpoints.

Recursive ↔ Forwarder

- Internal TLS tunnels or VPN to ensure queries between on-prem resolvers and cloud DNS are encrypted.

Forwarder ↔ Authoritative

- TSIG-secured zone transfers keep your internal zone data in sync without exposing it publicly.

Resolver ↔ Upstream/Root

- Outgoing DNSSEC-validating queries to root and TLD servers.

6. Logging & Monitoring Flows

Query Logs (stub → recursive)

- Captures source IP, requested name, timestamp, protocol (DoH/DoT/UDP).

Zone Transfer Logs (hidden primary → authoritative)

- Monitored via secure syslog or SIEM for unauthorized AXFR/IXFR attempts.

Security Events

- Protective DNS blocks trigger alerts in your SIEM/SOAR for automated incident response.

7. Example Scenario

- Step 1: Laptop stub sends DNS over HTTPS to Corporate Recursive Resolver.

- Step 2: Resolver checks its RPZ feed sees

malicious-site.comlisted. - Step 3: Resolver returns

NXDOMAIN(or redirect to a warning page). - Step 4: Resolver logs the blocked query (source = Alice’s IP, domain, timestamp) and forwards that log to SIEM.

- Step 5: SIEM rule triggers a SOC ticket or an automated SOAR playbook to quarantine the endpoint.

8. Key Takeaways

- Layered Security: Authenticate zone transfers (TSIG), validate records (DNSSEC), encrypt transport (DoH/DoT), and enforce policy (RPZ/firewall).

- Defence-in-Depth: No single control stops all threats combine cryptography, network controls, and logging.

- Visibility & Automation: Centralize logs into SIEM/SOAR to detect and respond to anomalies in real time.

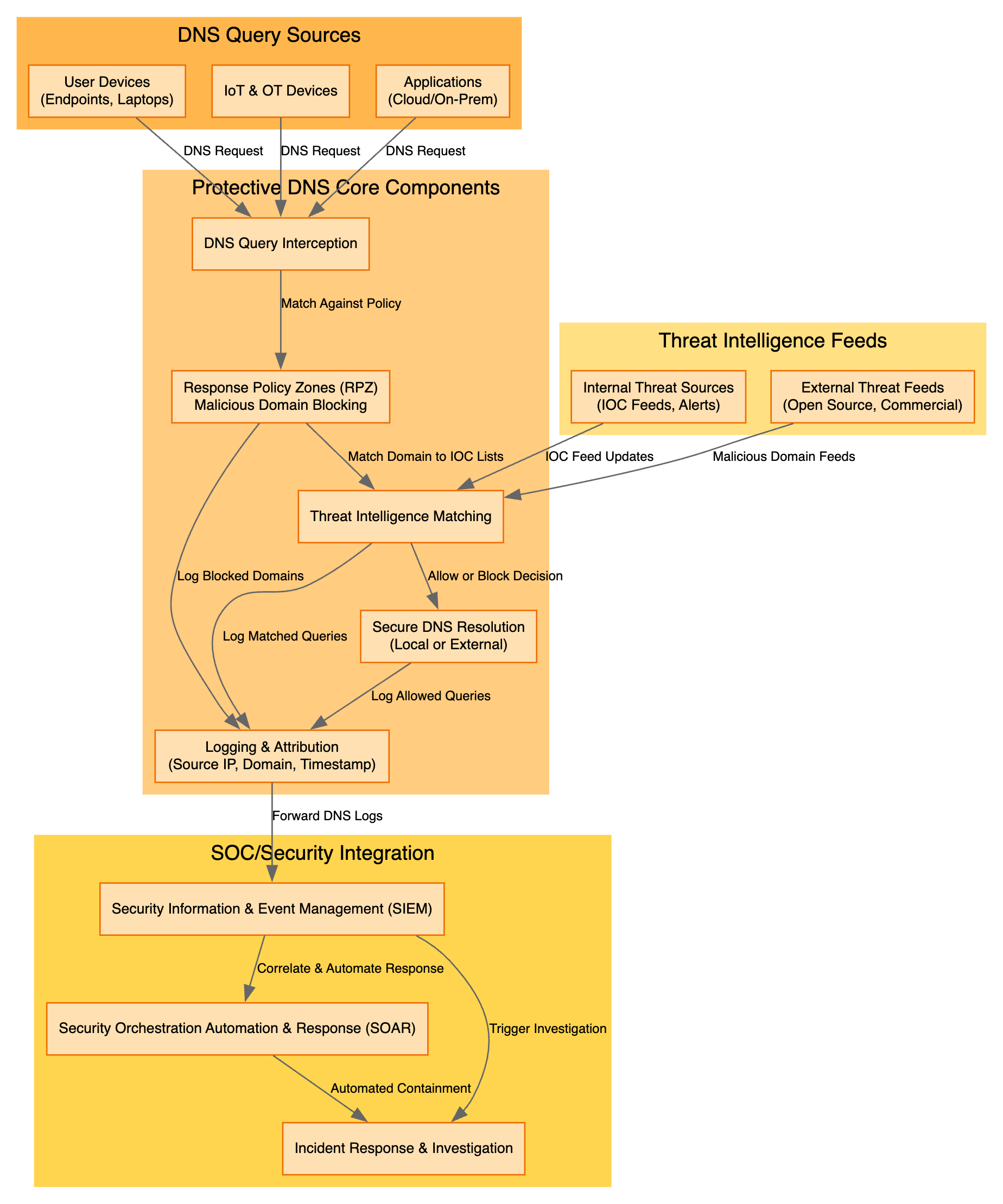

Part 2 – Protective DNS Functional Framework

1. What Is Protective DNS?

Protective DNS (sometimes called “DNS security”) sits between your users and the public DNS system to:

- Intercept every DNS query your devices send.

- Match each query against policies and threat feeds.

- Filter or block requests for known-malicious domains.

- Log all activity for downstream analysis.

- Feed alerts and events into your SOC toolkit (SIEM/SOAR).

Even if you’ve never configured a DNS firewall, this step-by-step breakdown will make it crystal clear.

2. Core Components & Data Flow

When a device on your network needs to resolve a name, the query is processed through several Protective DNS stages. Below is a step-by-step breakdown in pure Markdown:

DNS Query Sources

- Endpoints & Laptops

- IoT & OT Devices

- Cloud or On-Prem Applications

Each of these sends a standard DNS request (UDP/TCP on port 53, or encrypted DoH/DoT) toward your Protective DNS layer.

DNS Query Interception

- Transparent Proxy

- Network appliance intercepts all DNS traffic on-the-fly.

- Explicit Forwarder

- Endpoints are configured to point at your Protective DNS servers.

- Outcome: Every DNS request is captured and handed off to your policy engine.

- Transparent Proxy

Response Policy Zones (RPZ)

- A specialized “blocklist” zone loaded into your DNS server.

- Actions:

- Block (return NXDOMAIN)

- Redirect (reply with a warning IP)

- Rewrite (e.g. change

*.evil.com→safe.corp.local)

- When it runs: Immediately after interception, before any upstream resolution.

Threat Intelligence Matching

- Internal Feeds: IOC lists from your SOC (sandbox alerts, incident exports).

- External Feeds: Open-source lists (e.g. Spamhaus) or commercial subscriptions.

- Matching Logic:

- Check the queried domain against RPZ entries.

- If not in RPZ, check against fresh threat-intel lists.

- Apply any custom allow-lists or overrides.

- Decision: Allow or Block.

Secure DNS Resolution

- If Allowed:

- Forward the query to a recursive resolver (on-prem or cloud) over an encrypted channel (DoH/DoT).

- Return the final answer to the client.

- If Blocked:

- Immediately return NXDOMAIN or a redirect.

- Do not contact any upstream servers.

- If Allowed:

Logging & Attribution

- Log Fields:

- Source IP or device identifier

- Queried FQDN and record type

- Timestamp

- Action taken (Allowed, Blocked, Redirect)

- Policy or feed that triggered the block

- Storage/Forwarding:

- Local log files or database

- Forward to SIEM via syslog, JSON over HTTP, or other collector

- Log Fields:

SOC / Security Integration

- SIEM Ingestion: Correlate DNS events with firewall, endpoint, and application logs.

- SOAR Playbooks:

- Auto-quarantine compromised hosts on critical blocks.

- Generate incident tickets for manual review.

- Investigation & Response: SOC analysts leverage DNS logs to trace attacker activity and remediate.

By following these seven stages interception, RPZ, threat matching, resolution, logging, and SOC integration you ensure that every DNS lookup on your network is both protected and fully auditable.

3. Component Deep-Dive

3.1 DNS Query Interception

- How it works:

- Transparent proxy: network appliance intercepts port 53/443 traffic.

- Explicit forwarder: endpoints are configured to “point” at your Protective DNS server.

- Beginner tip: Think of it like a receptionist who takes every phone call (DNS query) before passing it on.

3.2 Response Policy Zones (RPZ)

- What it is: A special DNS zone that lists domains you want to block or redirect.

- Examples:

*.bad-malware.com → NXDOMAINdangerous-phish.net → 10.0.0.5(a local “warning” server)

- Why use it: RPZs are built into most enterprise DNS software easy to update and maintain.

3.3 Threat Intelligence Feeds

- Internal sources:

- Malware sandbox alerts

- Incident response IOC exports

- External feeds:

- Open-source lists (e.g. Spamhaus, Malware-domains)

- Commercial threat-intel subscriptions

- Flow:

- Feeds deliver domain lists (often hourly).

- RPZ zones or a matching engine load new entries automatically.

3.4 Threat Intelligence Matching

- Function: For each intercepted DNS query, compare the domain against:

- RPZ rules

- IOC lists

- Custom allow-lists (e.g.

*.trusted-partner.com)

- Result: A simple Allow or Block decision.

3.5 Secure DNS Resolution

- Allowed queries go to your recursive resolver or a cloud DNS service preferably over an encrypted channel (DoH/DoT).

- Blocked queries return an explicit NXDOMAIN or a “captive portal” IP to show a warning page.

3.6 Logging & Attribution

Every query yields a log record containing:

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Source IP/Host | Which device made the request |

| Domain Name | The FQDN or wildcard that was queried |

| Timestamp | When the query happened |

| Action | Allowed, Blocked (and by which policy/RPZ) |

Logs can be stored locally (flat files, databases) or forwarded to a SIEM.

3.7 SOC / Security Integration

- SIEM ingestion: DNS logs feed into your SIEM for correlation with firewall, endpoint, and application logs.

- SOAR automation:

- Auto-containment: If a critical domain is requested, trigger an endpoint quarantine playbook.

- Ticket creation: Automatically open an incident ticket for blocked queries from high-risk hosts.

- Outcome: Faster detection and response for DNS-based threats.

4. Example Scenario

- Interception: The thermostat’s DNS request is caught by your Protective DNS proxy.

- RPZ Check:

evil-c2.comis on your “blocklist” RPZ. - Threat Match: External commercial feed confirms

evil-c2.comis a known C2 domain. - Block Response: DNS server returns NXDOMAIN. The thermostat can’t resolve the address.

- Logging:

- Source:

10.10.5.42(thermostat) - Domain:

evil-c2.com - Action: Blocked by RPZ

- Source:

- SOC Alert: SIEM rule fires, SOAR playbook quarantines the thermostat VLAN and notifies the SOC team.

5. Key Takeaways

- Visibility: Every DNS lookup even from “dumb” IoT devices becomes an audit trail.

- Prevention: RPZ + threat feeds stop known-bad domains before a connection is ever attempted.

- Automation: Tight SIEM/SOAR integration turns DNS events into actionable security workflows.

- Scalability: Protective DNS scales from a small branch office appliance to global cloud services.

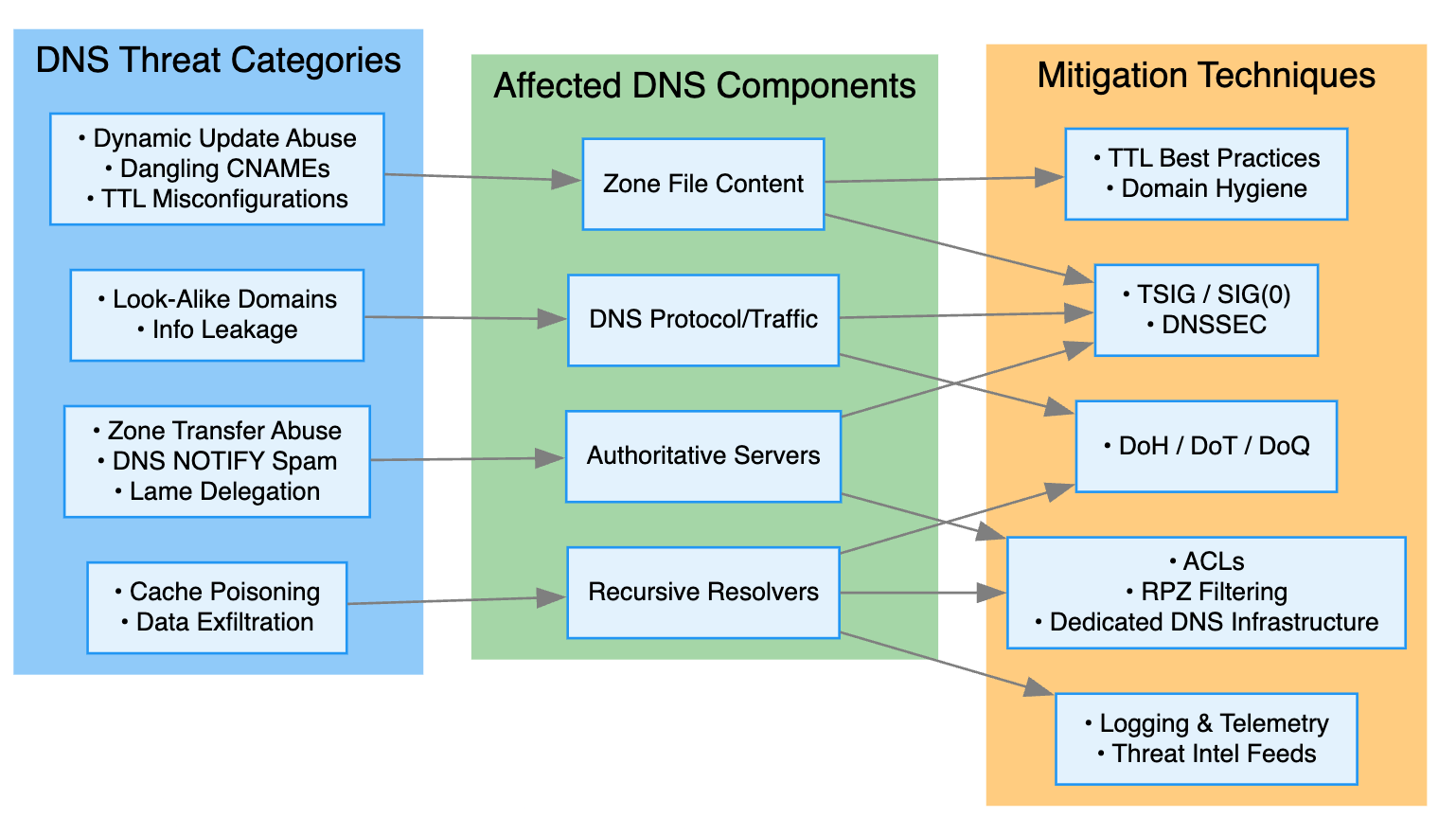

Part 3 – DNS Threats and Mitigation

1. Introduction

DNS is deceptively simple yet attackers exploit every layer, from zone files to transport protocols. This section breaks down:

- Threat Categories – the kinds of DNS attacks you might face

- Affected Components – which part of your DNS stack is under attack

- Mitigation Techniques – how to stop or limit each threat

Even if you’re new to DNS security, you’ll walk away knowing exactly which controls to apply where.

2. DNS Threat Categories

Dynamic Update Abuse & Zone File Misconfigurations

- Dangling CNAMEs (CNAME records pointing to non-existent names)

- Excessively long TTLs that delay clean-up or propagate stale entries

Look-Alike Domains & Information Leakage

- Typosquatting (

g00gle.comvs.google.com) - TXT record exposure leaking internal hostnames or credentials

- Typosquatting (

Zone Transfer Abuse & Lame Delegation

- Unauthorized AXFR/IXFR pulls entire zone contents

- DNS NOTIFY Spam floods secondaries with fake SOA change notifications

- Lame Delegation NS records pointing to unresponsive or unauthorized servers

Cache Poisoning & Data Exfiltration

- Cache Poisoning injecting false answers into a resolver’s cache

- DNS Tunneling encoding data into DNS queries for covert channels

3. Affected DNS Components

| Threat Category | Affected Component |

|---|---|

| Dynamic Update Abuse & TTL Misconfigs | Zone File Content |

| Look-Alike Domains & Info Leakage | DNS Protocol & Traffic |

| Zone Transfer Abuse & Lame Delegation | Authoritative Servers |

| Cache Poisoning & Data Exfiltration | Recursive Resolvers |

4. Threat → Component → Mitigation Mapping

Below is a quick-reference table summarizing the flow from attack type through to defense:

5. Example Scenario

- Attack: Attacker floods resolver with spoofed responses claiming

login.bank.com → 203.0.113.45(their malicious server). - Affected: The resolver’s cache would serve the fake IP to users.

- Mitigations Applied:

- Patch & Rate-limit: Upgrade to a patched resolver (randomized source ports).

- DNSSEC Validation: Enforce DNSSEC on upstream invalid signatures are dropped.

- RPZ Rule: Block lookups for known-bad C2 domains involved in the attack.

- Outcome: Spoofed responses are ignored; genuine bank IPs are returned.

6. Key Takeaways

- Layered Defenses: No single control suffices combine zone‐file hygiene, cryptographic signing, transport encryption, and access controls.

- Practice Good Hygiene: Regularly audit your zone files and tighten TTLs to limit exposure.

- Visibility Matters: Centralized logging and fresh threat feeds turn DNS from a blind spot into an early-warning sensor.

- Automate & Update: Keep your DNS software patched and threat-intel up to date to stay ahead of evolving attacks.

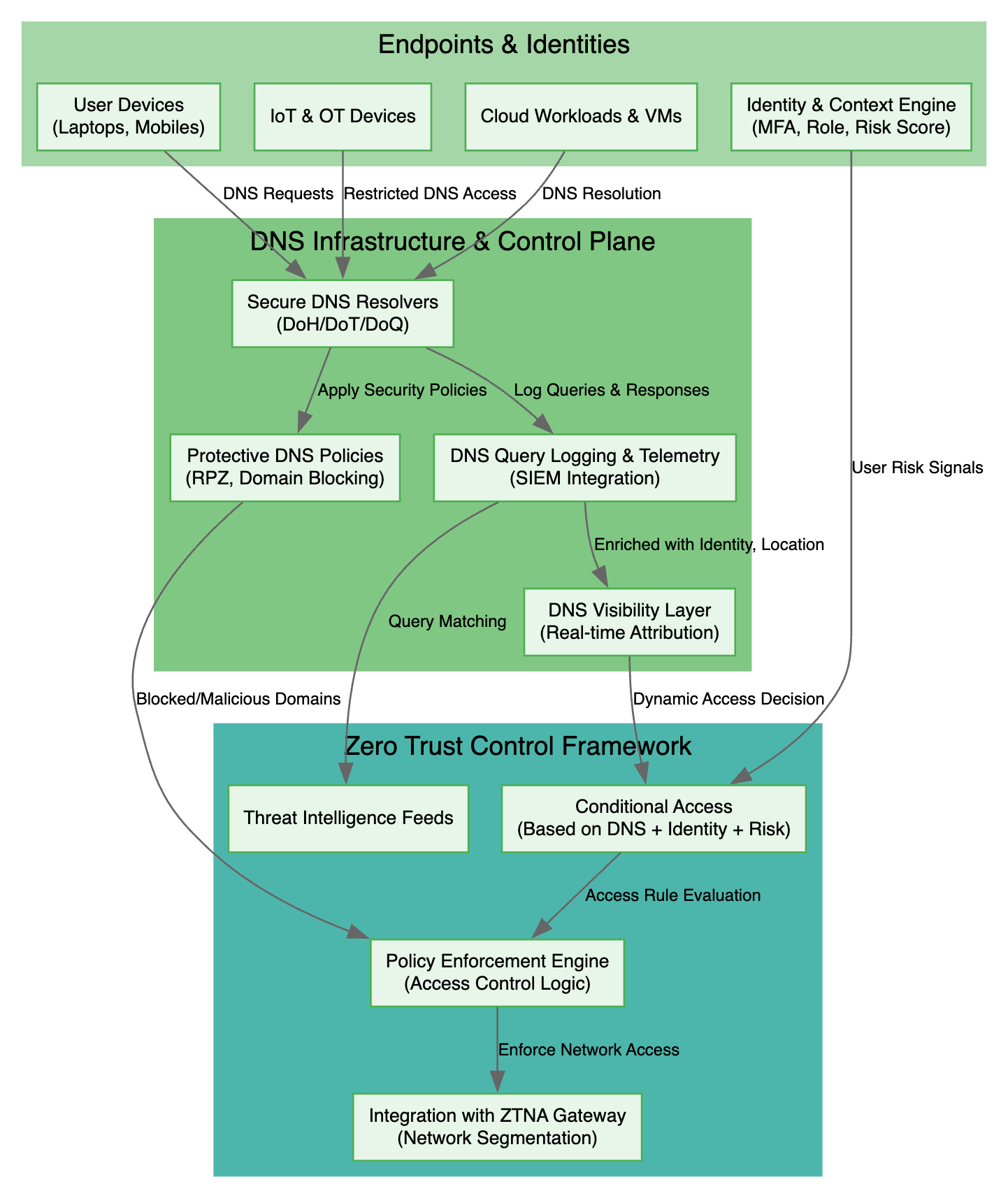

Part 4 – Zero Trust DNS Integration Diagram

1. Introduction

In a Zero Trust model, never trust, always verify applies to every network transaction including DNS lookups. Instead of assuming “on the corporate LAN = safe,” Zero Trust continuously evaluates who is asking, what they’re asking for, and where they are before allowing or blocking the DNS resolution.

2. Endpoints & Identities

Every DNS request carries context beyond just the domain name. To enforce Zero Trust, we first gather:

- User Devices (laptops, mobiles)

- Identity signals: username, device posture (managed vs. unmanaged), MFA status

- IoT & OT Devices

- Device IDs: serial numbers, certificate thumbprints, network segment

- Cloud Workloads & VMs

- Workload identity: workload certificates, pod labels, cloud-IAM roles

- Identity & Context Engine

- Combines MFA state, role, device risk score, geolocation, time-of-day, etc.

- Feeds risk signals into DNS policy decisions

3. DNS Infrastructure & Control Plane

DNS queries flow through a hardened control plane enriched with context:

Secure DNS Resolvers

- Accept only DoH/DoT/DoQ from authenticated, managed endpoints

- Enforce client certificates or VPN authentication

Protective DNS Policies

- RPZ or inline DNS firewall rules enriched with identity and risk signals

- Block or redirect domains based on threat intel and context

DNS Query Logging & Telemetry

- Every query/response logged with user, device, and location metadata

- Logs streamed in real time to SIEM for correlation

DNS Visibility Layer

- Maps each DNS event to user identity, device, and current risk score

- Enriched events feed downstream analytics (“Alice’s phone in London asked for

malware.test”)

4. Zero Trust Control Framework

DNS participates directly in your Zero Trust policy engine:

Threat Intelligence Feeds

- High-confidence blocklists push real-time updates into the policy engine

Conditional Access Policies

- Combine DNS + identity + risk to define rules, for example:

- “If device is unmanaged AND domain is high-risk → block.”

- “If device posture = compliant AND domain = partner-site → allow.”

- Combine DNS + identity + risk to define rules, for example:

Policy Enforcement Engine

- Evaluates each DNS request against conditional rules

- Produces an access decision: allow, block, or redirect

Integration with ZTNA Gateway

- Applies DNS decisions to network segmentation

- Blocked lookups never reach the corporate WAN; allowed queries get tunneled to the correct segment

5. Example Scenario

- Identity Check: VM lacks “managed endpoint” certificate; risk score = high.

- Policy Rule: “Block internal zones from unmanaged devices.”

- DNS Decision: Resolver returns NXDOMAIN for

confidential.corp.internal. - ZTNA Enforcement: Gateway drops any subsequent traffic to that IP.

- Alert & Log: SIEM raises an alert SOC sees an unmanaged host probing internal assets.

6. Key Takeaways

- DNS as a Control Point: DNS isn’t just name lookup it’s a rich signal for Zero Trust.

- Contextual Decisions: Combine identity, posture, and threat intel for dynamic allow/block.

- End-to-End Visibility: Every query is authenticated, logged, and attributed from stub to SIEM.

- Seamless Enforcement: ZTNA integration ensures DNS decisions translate to real-time network segmentation.

Conclusion

By layering cryptographic signing, encrypted transfers, threat-blocking rules, and continuous identity checks, you turn DNS from a weak spot into a powerful security gatekeeper. Follow the four views in this series and you’ll have a clear, step-by-step map to build, monitor, defend, and integrate DNS into a Zero Trust architecture no prior DNS experience required.

Reference

- I learned a lot from the NIST guide and then I simplified this guide into this blog - https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/81/r3/ipd