Threat Modeling Isn’t Just for Paranoids: Getting Real with STRIDE

Ever pushed code feeling pretty darn good about it, only to have that sinking feeling when a security issue pops up later? Yeah, me too. 13 years in this industry, and I can tell you, surprises in security are rarely the good kind. We build complex systems, juggling features, deadlines, and performance, and sometimes, just sometimes, security feels like this mystical thing we bolt on at the end, hoping for the best. But hope, as they say, isn’t a strategy, especially not in cybersecurity.

That’s where threat modeling comes in. Threat modeling is a practical, engineering discipline. It’s about proactively looking at your system before the bad guys do, figuring out where the weaknesses might be, and fixing them before they become headlines. It’s about shifting security left, making it part of the design conversation, not just an afterthought during a frantic incident response.

Now, there are various ways to approach threat modeling, but one framework that’s stood the test of time, especially for folks building software, is STRIDE that helps us systematically brainstorm how things could go wrong. It gives us a common language and a structured way to think about potential attacks.

We are going to ditch the overly academic jargon and get practical. We will break down what STRIDE is, walk through how to actually use it with three different real-world-ish scenarios (think APIs, IoT, and cloud platforms), share some hard-won tips from the trenches, and even suggest some ways you could visualize this stuff later on.

My goal here isn’t just to define STRIDE, but to show you how it can become a valuable tool in your engineering toolkit. It’s about making security less scary and more systematic. So, grab a coffee, settle in, and let’s talk about how to stride confidently towards more secure systems.

Getting Cozy with STRIDE: More Than Just a Long Walk

The magic of STRIDE lies in its acronym, which covers six key categories of security threats. When you are looking at a system component – whether it’s a user logging in, data moving across a network, or a file being saved – you ask yourself: how could someone mess with this using one of the STRIDE methods?

Let’s break down the letters:

S - Spoofing: This is all about impersonation. An attacker pretends to be someone or something they’re not. Think fake login pages trying to steal your credentials, or a malicious server mimicking a legitimate one to intercept data. The security property being violated here is Authenticity. Are you really talking to who you think you are talking to? Is that user really who they claim to be?

T - Tampering: This one’s about unauthorized modification. Attackers mess with data – maybe changing values in a database, altering code as it runs, or modifying data packets flying across the network. Imagine someone changing the amount on a financial transaction or tweaking configuration files to gain an advantage. The property under attack is Integrity. Can you trust that your data and your system haven’t been illicitly changed?

R - Repudiation: This is the “I didn’t do it!” threat. An attacker performs some malicious action and then tries to deny having done it. Or, perhaps more commonly, the system simply lacks the ability to prove who did what. If you can’t prove a user placed that order or deleted that critical file, you have a repudiation problem. The violated property here is **Non-**repudiability. Can you trace actions back to the actor responsible?

I - Information Disclosure: This is about confidentiality breaches. Sensitive information gets exposed to people who shouldn’t see it. This could be anything from error messages revealing system internals, to attackers accessing private user data, to sniffing unencrypted network traffic. The property at stake is Confidentiality. Is your sensitive data kept secret from unauthorized eyes?

D - Denial of Service (DoS): Pretty self-explanatory – making a system or service unavailable to legitimate users. This could be by overwhelming it with traffic (like a classic flood attack), crashing a service, or locking out user accounts. The violated property is Availability. Can authorized users access the system and its data when they need to?

E - Elevation of Privilege: This is when someone gains more permissions than they should have. A regular user somehow gets admin rights, or one application component manages to execute code with the privileges of another, more trusted component. This is often the goal that enables other attacks. The violated property is Authorization. Are users and components restricted to only the actions and data they are explicitly allowed to access?

So if I were to summarize all of these in a single table, it would be something like this:

| Letter | Threat Type | Description | Violated Security Property | Example Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | Spoofing | Impersonation of users or systems. | Authenticity | Fake login pages, malicious servers intercepting data. |

| T | Tampering | Unauthorized data/code modification. | Integrity | Altering database values, changing code or config files. |

| R | Repudiation | Denial of performed actions due to lack of accountability. | Non-repudiability | No audit trail for deleted files or transactions. |

| I | Information Disclosure | Exposure of confidential information to unauthorized entities. | Confidentiality | Leaked error messages, sniffed traffic, internal data exposed. |

| D | Denial of Service (DoS) | System made unavailable to legitimate users. | Availability | Flooding traffic, service crashes, user lockouts. |

| E | Elevation of Privilege | Gaining unauthorized access or higher privileges than allowed. | Authorization | Regular user gaining admin rights, untrusted code gaining system privileges. |

Why STRIDE Rocks (and When to Use It)

So, why has STRIDE stuck around? A few reasons:

- It’s systematic: It forces you to think through different types of attacks, reducing the chance you will miss something obvious because you were only focused on, say, injection attacks.

- Common language: It gives teams a shared vocabulary. Talking about a potential “Tampering” threat is clearer than vague hand-waving about security.

- Good coverage: While not exhaustive (no framework is), it covers the major ways software systems get compromised.

- Relatively simple: Compared to some other methodologies, STRIDE is fairly easy to grasp and start applying.

Ideally, you want to apply STRIDE during the design phase of the software development lifecycle (SDLC). Finding a flaw on a whiteboard is infinitely cheaper and easier to fix than finding it in production code. However, it’s never too late. You can apply STRIDE to existing systems, new features, or even specific changes to understand the security implications.

Now that we know what STRIDE is, let’s look at how to actually put it into practice.

Summary of The Approach

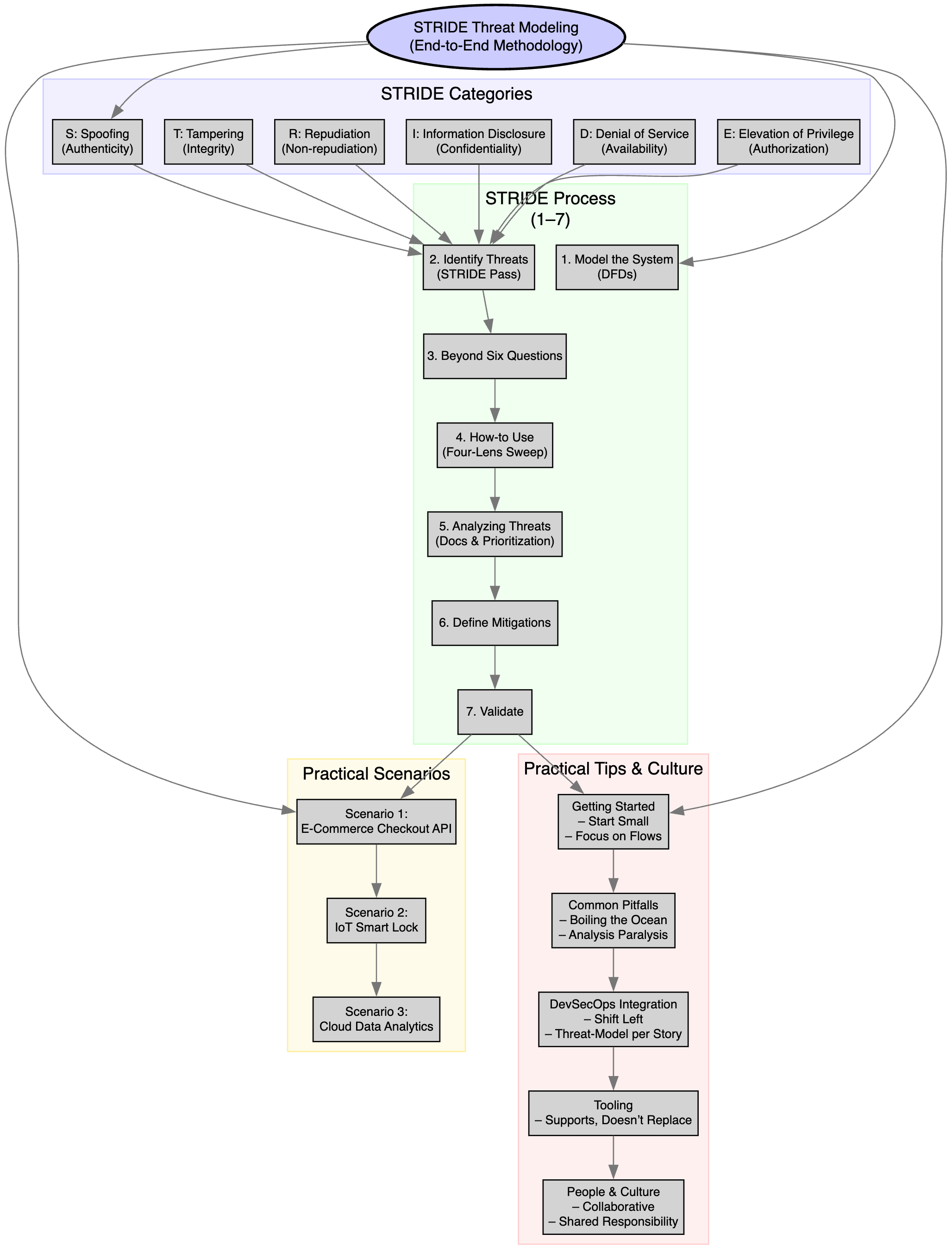

Before we go deep into this novel approach, let me summarize the overall process from this article in a simplistic diagram.

The STRIDE Process: From Theory to Action

Before we go deep into process, let’s look at the high level process how does it look like:

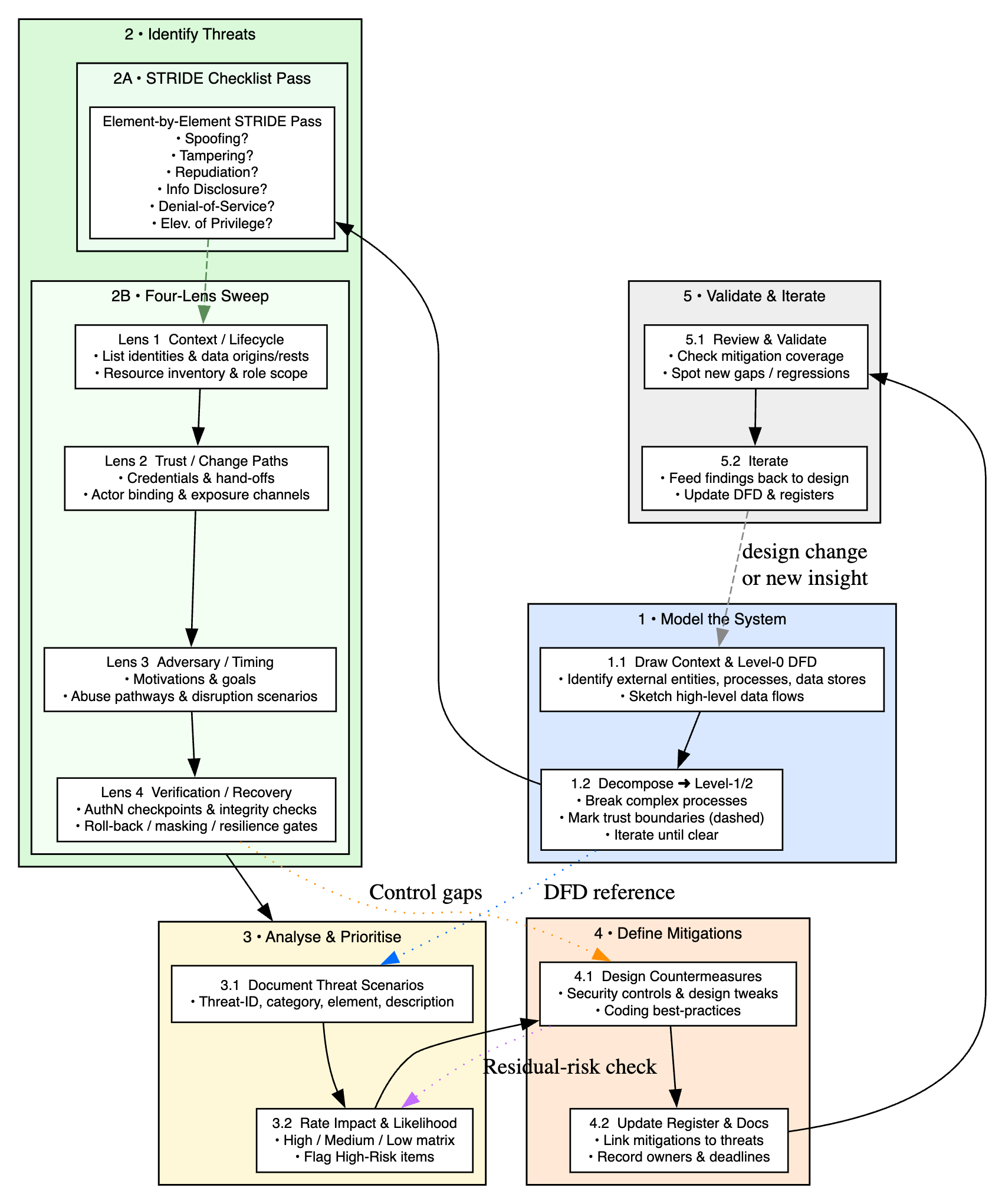

Okay, we know the what (the STRIDE categories) and the why (proactive security!). Now, let’s get into the how. How do you actually do a STRIDE analysis? It’s not just about chanting the acronym; it’s a process. Here’s a typical flow, keeping in mind this can be adapted:

1. Model the system (draw the map)

You can’t find threats in something you don’t understand. The first step is always to visualize the system you are analyzing. The most common way to do this in threat modeling is using Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs). A DFD is just a structured way to show how data moves through your system. Key symbols you will use are:

- External entities: Squares representing users, other systems, or anything outside your system boundary that interacts with it.

- Processes: Circles representing activities or functions that transform data (e.g., ‘Validate Payment’, ‘Update Inventory’).

- Data stores: Two parallel lines representing where data rests (e.g., ‘User Database’, ‘Order Cache’).

- Data flows: Arrows showing the movement of data between entities, processes, and stores.

- Trust boundaries: Dashed or dotted lines indicating where the level of trust changes (e.g., between the public internet and your internal network, or between a user process and an admin process). Start high-level and decompose complex processes into lower-level DFDs if needed. The goal is clarity, not artistic perfection.

2. Identify threats (The STRIDE Pass)

This is where the STRIDE mnemonic shines. Go through your DFD, element by element (each process, data store, data flow, and even external entity interaction). For each element, systematically ask the STRIDE questions:

- How could an attacker Spoof this entity or process?

- How could someone Tamper with this data flow or data store?

- Could an action involving this element be Repudiated?

- Could Information be improperly Disclosed from this element or flow?

- Could this process or data store be subject to Denial of Service?

- Could an attacker achieve Elevation of Privilege through this element? Focus especially on data flows crossing trust boundaries – these are often hotspots for vulnerabilities.

3. Going Beyond “Just Six Questions”

Most guides you will find online stop at the simple STRIDE checklist:

- How could this be Spoofed?

- How could it be Tampered with?

- Could someone Repudiate the action?

- Might Information be Disclosed?

- Could this element suffer a Denial-of-Service?

- Is there a path to Elevate Privilege?

That’s a useful starting point but it leaves you asking the same six questions over and over, without telling you how to think about where the gaps actually live or why an attacker would exploit them. You end up with a bullet list of “possible threats” rather than a rich map of all the angles you need to sweep.

To fill that gap, I have developed a 360° thinking blueprint for each STRIDE category, four complementary “lenses” you can peer through, a mini-checklist of red-flags, and reflective prompts to spark concrete scenarios. Use it against any DFD element, at any level (1/2), and you will move from rote questions to real insight: precisely where your system is vulnerable, how an attacker might work their way in, and what defenses belong at each step.

Below you will find the full blueprint your new go-to process whenever you sit down with a whiteboard or a DFD.

Spoofing (Authenticity)

- Make sure every participant really is who they claim to be.

| Lens | What to Explore / Do | Mini-Checklist | Reflective Prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context & Scope | Define exactly where “identity” matters; list every human, service or system identity in this element. | – Missing or default accounts? - Shared or hard-coded credentials? | • What or who is assumed genuine here? • Where does belief begin or end? |

| Trust Relationships | Map who trusts whom and on what basis; spot every credential handshake. | – One-way authentication only? – Weak or missing proof? | • Who is counting on this proof of identity? • What minimal cue grants trust? |

| Adversary Motivation | Imagine why someone would pretend to be this entity; enumerate replay, cloning or masquerade tactics. | – Replayable tokens? – Lack of anti-replay checks? | • What’s the upside for an imposter? • How could they gain advantage? |

| Verification Points | Spot every moment identity is (or isn’t) checked; consider where mutual checks or external roots apply. | – No mutual proof? – Missing challenge-response? | • How would you prove it’s really them? • Where could that proof be faked? |

Tampering (Integrity)

Catch any unauthorized change to data, code or decisions.

| Lens | What to Explore / Do | Mini-Checklist | Reflective Prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifecycle View | Trace where data or logic is created, stored or transformed; list flows, caches, temp stores. | – Plaintext in flight? – Writable surfaces? | • When/where does the “original” exist? • Where could it be altered unseen? |

| Change & Update Paths | Identify every hand-off, deployment, patch or update process. | – Unsigned artifacts? – Missing checksum validation? | • What hand-off could go wrong? • Where could an extra change slip in? |

| Adversary Goals | Consider why an attacker would corrupt this element; think interception, direct writes, replays. | – MITM possible? – Unchecked replay? | • What would they gain by tweaking it? • Which distortions best serve their aim? |

| Validation & Recovery | Review how illicit changes are detected or rolled back; integrity checks and recovery mechanisms. | – No tamper alerts? – Missing backup/rollback plan? | • How would you know it’s been altered? • What resets it to “known good”? |

Repudiation (Non-repudiation)

- Guarantee every action leaves a clear, unforgeable trail.

| Lens | What to Explore / Do | Mini-Checklist | Reflective Prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Action Points | List every critical operation deletes, transfers, approvals where proof may be needed. | – Missing audit hooks? – Anonymous/shared actions? | • Which steps matter legally or financially? • What counts as “proof”? |

| Actor Binding | Ensure each log entry ties to a unique, non-shareable originator (user ID, session, request ID). | – Shared sessions? – Session hijacking risks? | • How do you link deed to doer? • Could someone hide behind a shared handle? |

| Temporal Context | Anchor events with unambiguous timestamps and ordering; account for clock skew and sequence. | – Missing timestamps? – Easily adjusted clocks? | • When did it happen and why does sequence matter? • Could times be contested? |

| Audit Assurance | Protect logs from tampering or deletion consider append-only, off-site archives and strict controls. | – Editable logs? – Insecure log transport? | • How would you spot log tampering? • Where would you look first? |

Information Disclosure (Confidentiality)

- Keep every secret and private detail from leaking.

| Lens | What to Explore / Do | Mini-Checklist | Reflective Prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sensitivity | Classify each piece of information (public, internal, secret, PII) and note its hiding requirements. | – Misclassified data? – Unlabeled secrets? | • How damaging if this got out? • Who must stay ignorant? |

| Exposure Channels | Enumerate all ways info might slip APIs, logs, UIs, error messages, backups, side-channels. | – Verbose stack traces? – Open debug endpoints? | • Where might a whisper become public? • What side-paths exist? |

| Adversary Benefits | Envision motives for extracting each data type and map potential misuse. | – Valuable metadata exposed? – No usage monitoring? | • Who gains from knowing this? • How would they exploit it? |

| Masking & Purge | Plan how to obscure or destroy residual copies temp files, caches, logs. | – Unremoved temp files? – Long log retention? | • How would you blur it? • How do you erase every copy? |

Denial of Service (Availability)

- Keep the system usable even under strain or attack.

| Lens | What to Explore / Do | Mini-Checklist | Reflective Prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resource Inventory | List all critical resources CPU, memory, threads, connections and map consumption patterns. | – Unbounded allocations? – No quotas? | • What do people expect always works? • What would they miss first? |

| Demand Patterns | Analyze normal vs. peak usage seasonal spikes, bursts, user behavior extremes. | – Unexpected spikes? – Resource starvation? | • When do demands spike? • What breaks under unusual stress? |

| Disruption Scenarios | Imagine deliberate or accidental overloads, partial failures, dependency breakdowns. | – Retry storms? – Unhandled errors? | • How might service be disrupted? • What small hiccups cascade? |

| Resilience Measures | Spot controls rate limits, circuit breakers, graceful degradation, fail-over and back-pressure. | – No rate limiting? – Missing failover paths? | • How does it bounce back? • Where is the “safety net”? |

Elevation of Privilege (Authorization)

- Stop anyone gaining more rights than intended.

| Lens | What to Explore / Do | Mini-Checklist | Reflective Prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role & Scope Mapping | Define every role, permission set and boundary; note defaults and inheritance. | – Over-permissive defaults? – Role explosion? | • Who can do what and why? • Where might those lines blur? |

| Interaction Flows | Chart every path APIs, UIs, batch jobs to sensitive operations, including indirect or hidden routes. | – Hidden/end-of-life endpoints? – Unprotected APIs? | • How do they reach a sensitive operation? • What shortcuts could be abused? |

| Abuse Pathways | Envision detours callbacks, escalation loops, side-channels that grant extra power. | – Orphaned admin functions? – Unchecked callbacks? | • What’s an unlikely shortcut to admin? • Where could checks be skipped? |

| Enforcement Checks | Verify authorization at every critical step before and after and spot missing or inconsistent checks. | – Missing post-action checks? – Inconsistent gating? | • When do you ask “Is this allowed?” • Where might that check be missing? |

4. How-to use

Select your DFD element

- Pick one bubble, arrow or datastore on your diagram.

- Note its name, purpose and where it sits in the overall flow.

Determine Which STRIDE Category(ies) to Apply

- Every element potentially touches all six but start by mapping it to the most obvious threat types.

- E.g. a “Login Service” ⇒ Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, DoS.

- You can circle all six at first to ensure full coverage.

Run the Four-Lens Sweep for Each STRIDE Category For each category you have marked, work through the four lenses in order:

- A. Lens 1 (Context & Scope / Lifecycle View / Action Points / Data Sensitivity / Resource Inventory / Role & Scope Mapping)

- What to do: Define the boundaries and key facts.

- Context & Scope: Who or what identities appear here?

- Lifecycle View: When and where does data/code originate and rest?

- Action Points: Which operations must be provable?

- Data Sensitivity: How secret is the information?

- Resource Inventory: What resources (CPU, memory, threads) does this element consume?

- Role & Scope Mapping: Which roles and permissions live here?

- Output: A crisp bullet list of your findings (e.g., “this datastore holds PII; it’s written to by two processes; default service account exists”).

- Lens 2 (Trust Relationships / Change & Update Paths / Actor Binding / Exposure Channels / Demand Patterns / Interaction Flows)

- What to do: Map hand-offs, hand-backs, and who trusts whom.

- Trust Relationships: What proofs or credentials pass through?

- Change & Update: How does code/config get deployed here?

- Actor Binding: How do you tie each action back to one originator?

- Exposure Channels: Through which paths could data leak?

- Demand Patterns: When does this element see normal vs. bursty load?

- Interaction Flows: What direct or hidden routes lead to privileged operations?

- Output: A mini-diagram or bullet list noting each handshake, update path, log binding, channel, load characteristic or interaction route.

- C. Lens 3 (Adversary Motivation / Adversary Goals / Temporal Context / Adversary Benefits / Disruption Scenarios / Abuse Pathways)

- What to do: Step into an attacker’s shoes why and how would they target this element?

- Adversary Motivation: What’s the payoff for impersonation or data alteration?

- Adversary Goals: What integrity breaks or privilege gains serve them best?

- Temporal Context: How might timing or sequencing be manipulated?

- Adversary Benefits: Which secrets or resources are most valuable here?

- Disruption Scenarios: How could they trigger overloads or failures?

- Abuse Pathways: What unexpected detours grant extra power?

- Output: Three to five concrete “what if” scenarios (e.g., “what if they replayed a token at peak hour to lock out users?”).

- D. Lens 4 (Verification Points / Validation & Recovery / Audit Assurance / Masking & Purge / Resilience Measures / Enforcement Checks)

- What to do: Identify how you’d detect, stop or recover from each potential attack.

- Verification Points: Where do you check authenticity?

- Validation & Recovery: How do you detect and roll back tampering?

- Audit Assurance: How do you guarantee log integrity?

- Masking & Purge: How do you obscure or erase sensitive traces?

- Resilience Measures: What rate limits, fail-overs or fallbacks exist?

- Enforcement Checks: Where are authorization gates, before and after?

- Output: A list of existing controls and any gaps (e.g., “no replay-guard on tokens; rollback plan only covers DB rows, not caches”).

- Quickly rate each scenario for Impact (High/Med/Low) and Likelihood (High/Med/Low).

- Focus first on those in the High-High and High-Med zones.

- Once one element is done, move to the next.

- Revisit high-level trust boundaries and data flows to see cross-element interactions.

- Walk through your findings with teammates developers, architects, testers, ops.

- Confirm that your mitigation ideas line up with real-world constraints and that no new gaps emerge.

- Make this four-lens sweep part of design reviews or “definition of done” for major stories.

- Keep your threat register live and revisit it whenever designs change.

5. Analyzing Threats (Documentation and Prioritization)

As you identify potential threats, document them! A simple list or spreadsheet works fine. Include:

- For each lens’s reflective prompts and mini-checklist red flags, turn your notes into formal “threat scenarios.”

- Use a simple table or spreadsheet with columns:

- ID (e.g., SPOOF-01)

- Category (Spoofing, Tampering, …)

- Element (Login Service, Order DB, etc.)

- Threat Description (concise “how” + “why”)

- Detection/Mitigation Ideas (from Lens 4)

- Quickly rate each scenario for Impact (High/Med/Low) and Likelihood (High/Med/Low).

- Focus first on those in the High-High and High-Med zones.

- Once one element is done, move to the next.

- Revisit high-level trust boundaries and data flows to see cross-element interactions.

6. Define Mitigations (Plan the Fixes)

For the threats you have decided are worth addressing (usually the higher-risk ones), brainstorm countermeasures. What security controls, design changes, or coding practices can prevent or mitigate this threat? Document these proposed mitigations alongside the threats. Walk through your findings with teammates developers, architects, testers, ops.Confirm that your mitigation ideas line up with real-world constraints and that no new gaps emerge.Make this four-lens sweep part of design reviews or “definition of done” for major stories.

7. Validate (Check Your Work)

Review the identified threats and proposed mitigations. Do the mitigations actually address the threats? Are there any gaps? Does implementing one mitigation introduce another threat? This is often an iterative process. Keep your threat register live and revisit it whenever designs change.

This might seem like a lot, but starting small and focusing on critical parts of your system makes it manageable. Now, let’s see this process in action with a few scenarios.

Scenario 1: Securing an E-Commerce Checkout API

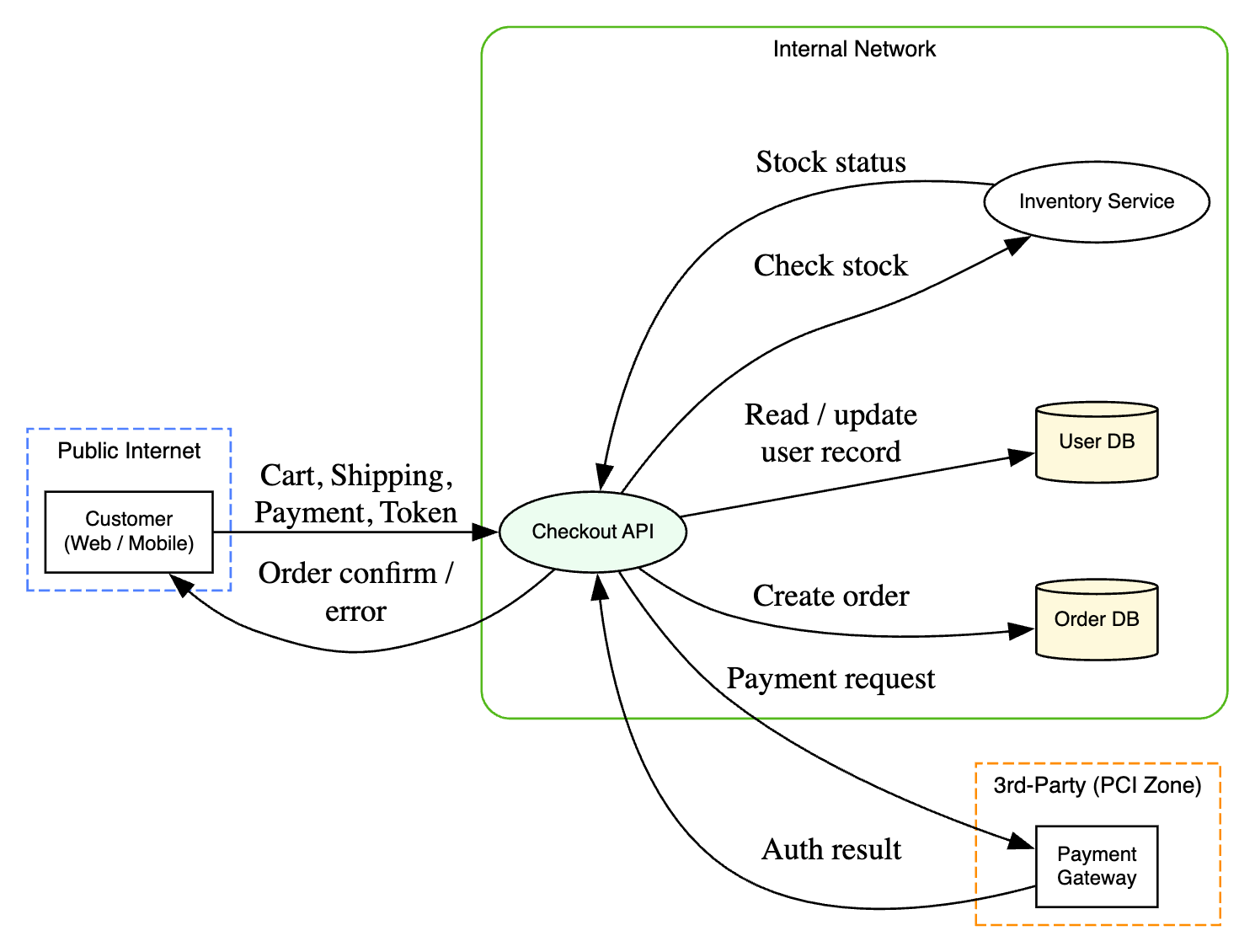

Theory is great, but let’s see STRIDE in action. Imagine we are building a core piece of an e-commerce platform: the Checkout API. This is a backend REST API, likely written in something like Python, Java, or Node.js.

System Overview

Its job is to handle the final stage of a purchase. It receives details from the customer’s frontend (web or mobile app), including:

- Items in the cart

- Shipping address

- Payment information (maybe tokenized card details or similar)

- User authentication token/session ID

Internally, this API needs to interact with several other components:

- Payment Gateway: An external service to process the actual payment.

- Order Database: An internal database to store details of the completed order.

- User Database: An internal database to retrieve/verify user details (like shipping address) and potentially update purchase history.

- Inventory Service: (Potentially) An internal service to check stock levels before finalizing the order.

Data Flow Diagram (DFD)

- Level 1 DFD

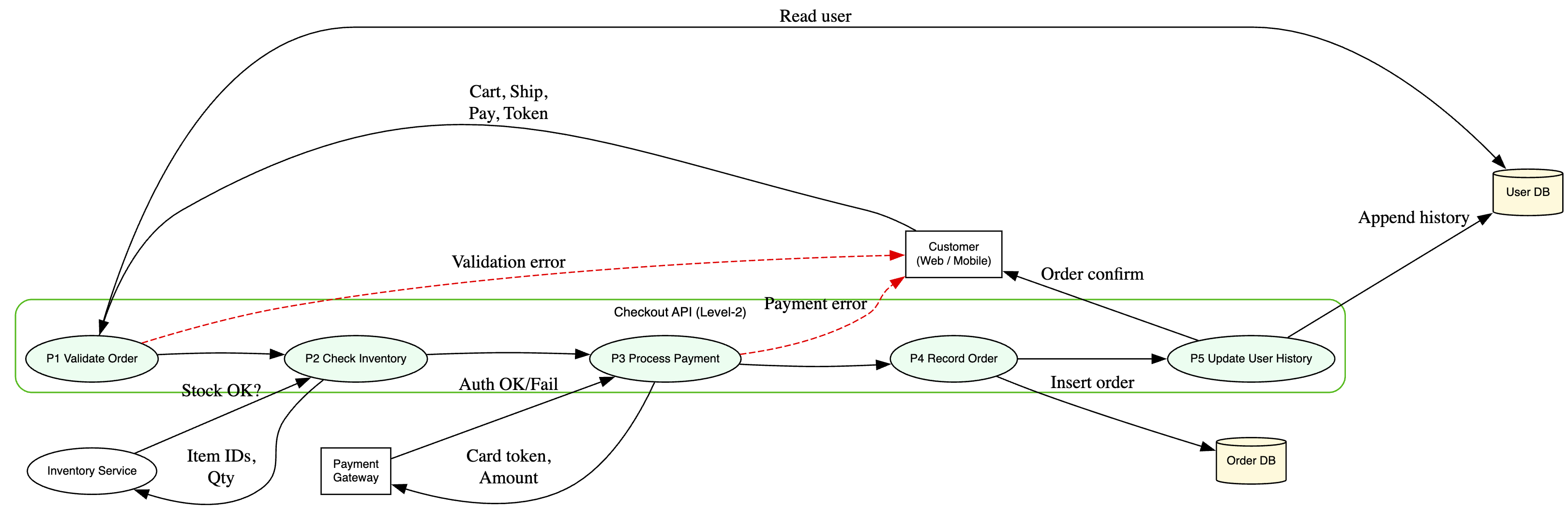

- Level 2 DFD

- External Entities: Customer (via Frontend App), Payment Gateway.

- Processes: Checkout API, (maybe separate internal processes like Validate Order, Process Payment, Update Database).

- Data Stores: Order Database, User Database, (maybe Inventory Database).

- Data Flows:

- Customer -> Checkout API (Cart details, Payment info, Auth token)

- Checkout API -> Payment Gateway (Payment details, Amount)

- Payment Gateway -> Checkout API (Payment success/failure)

- Checkout API -> Order Database (New order details)

- Checkout API -> User Database (Read user info, maybe write purchase history)

- Checkout API -> Inventory Service (Check stock)

- Inventory Service -> Checkout API (Stock status)

- Checkout API -> Customer (Order confirmation/error)

- Trust Boundaries: Between Customer & API, between API & Payment Gateway, between API & internal databases/services.

Applying STRIDE

Methodology

- Select your DFD element (Scope Identification)

- Identify the component (e.g. Checkout API, Auth Service, Web App, Payment Gateway, etc.).

- Document its purpose, trust boundaries, and data flows in/out.

- For each STRIDE category, apply the 4 lenses. For each category:

- Lens 1 - Lifecycle View - List the assets (e.g. JWTs, cart payloads, logs) and their states (at rest, in transit, in memory).

- Lens 2 – Change & Update Paths - Map how those assets or code/configuration change or propagate (e.g. CI/CD deploys, feature-flag updates, log shipping).

- Lens 3 - Adversary Goals (“What-If”) - Define why an attacker would target this (e.g. under-pay, impersonate, exfiltrate data). Sketch a concrete “What if…” scenario.

- Lens 4 – Validation & Recovery - List existing controls (e.g. HTTPS, unit tests, rate-limits). Identify gaps where those controls fall short.

Repeat for every STRIDE category - Do this in turn for Spoofing, Tampering, Repudiation, Information Disclosure, DoS, Elevation of Privilege for each DFD element in your scope.

Consolidate into threat register table

- Create a table with below columns:

- ID (e.g. S-01, T-01, …)

- Element (DFD component)

- STRIDE

- Description

- Key Mitigations

- Impact

- Likelihood

Example for Applying Methodology

1. Select the DFD element

Element: P1 –> Checkout API

- Purpose: Finalizes a purchase by validting user, processing payment, updating database, and returning confirmation.

- Trust boundaries:

- Customer ↔ API (public Internet)

- API ↔ Payment Gateway (PCI zone)

- API ↔ internal services/databases (internal network).

Key data flows into/out of P1:

- In: Cart details + auth token (from Customer)

- Out: Payment request (to Gateway), order writes (to Order DB), user history update (to User DB), confirmation (to Customer).

2. STRIDE categories applicable for this functionality

We will cover all 6 threat types against this P1 element, each with 4 lens sweep.

| STRIDE | Violated Property |

|---|---|

| Spoofing | Authenticity |

| Tampering | Integrity |

| Repudiation | Non-repudiation |

| Information Disclosure | Confidentiality |

| DoS | Availability |

| Elevation of Privilege | Authorization |

3. Four-Lens Analysis for “Tampering” (Integrity) on the Checkout API

Lens 1: Lifecycle View

- Data origins & resting points:

- Cart payload (client → API)

- In-flight JSON bodies

- Temporary in-memory order object before DB write

- Red flags: client-calculated totals; no server-side checksum .

Lens 2: Change & Update Paths

- Hand-offs: API code deployed via CI/CD pipeline (unsigned artifacts?)

- Runtime patching: Hot restarts without integrity checks on new code .

Lens 3: Adversary Goals

- Why tamper? Under-charge orders or inject fraudulent discounts.

- Concrete “what-if”: “What if attacker intercepts and rewrites price in transit?”

Lens 4: Validation & Recovery

- Existing controls: HTTPS enforced, but no HSTS preload; unit tests only cover happy-path.

- Gaps: no server-side price recalculation; no integrity‐check on payload.

Threat Scenario (TAMP-01): Attacker modifies totalAmount in the JSON payload (e.g. 100 → 1) before TLS termination on a misconfigured segment, causing under-priced order.

- Mitigations:

- Recalculate order total server-side from SKU+qty

- Enforce HSTS + preload; block HTTP POSTs at WAF

- Add a signature (HMAC) over the cart contents

- Impact:

- High

- Likelihood:

- Medium

4. Threat Register Excerpt for Checkout API

| ID | Category | Threat Description | Detection & Mitigation | Impact | Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPOOF-01 | Spoofing | Stolen JWT is replayed to /checkout, impersonating another user and placing fraudulent orders. | Short-lived rotating tokens; token-binding to TLS; device-fingerprint check; SIEM rule detecting same token from multiple IPs. | High | Medium |

| TAMP-01 | Tampering | Attacker alters totalAmount in transit before the API, resulting in an under-priced order. | Server-side price calculation; enforce HSTS+preload; HMAC signature on payload; WAF HTTP enforcement. | High | Medium |

| REPU-01 | Repudiation | Only order IDs are logged; user claims “I never placed this order” and you lack IP/jti linkage for non-repudiation. | Append IP, JWT_jti, timestamp, request hash to immutable WORM log; support dispute workflow querying full audit by order ID. | Medium | Medium |

| INFO-01 | Information Disclosure | Unhandled exceptions in payment sub-process return full stack traces to clients, leaking internal hostnames and DB credentials. | Global error handler returns generic error codes; verbose traces only in internal logs; CI scans responses for “Exception in thread”. | Medium | Low |

| DOS-01 | Denial of Service | Botnet floods /checkout at high RPS, exhausting DB connections and external calls, preventing legitimate purchases. | API-gateway rate-limiting by IP/user; queue + worker pool autoscaling; alerting on latency and error spike. | High | Medium |

| ELEV-01 | Elevation of Privilege | Front-end sends a role field; naïve API trusts it and grants admin privileges for order modification. | JSON-schema strips unknown fields; derive role from authenticated session only; post-auth RBAC checks; integration tests for field injection. | High | Low |

5. Prioritization & Next Steps

- High Impact–Medium Likelihood threats (SPOOF-01, TAMP-01, DOS-01) should be addressed first.

- Integrate these controls into the CI/CD pipeline and definition of done for the Checkout feature.

- Retain and extend the threat register as the design evolves, and revisit during design reviews and pen-tests .

This demonstrates the exact four-lens STRIDE approach from your document, applied end-to-end to the Checkout API scenario.

Likewise once you complete this activity end-to-end for both diagrams and entire feature/functionality, your final threat register would look something like below:

| ID | Element | STRIDE | Description | Key Mitigations | Impact | Likelihood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-01 | Web App / Login | Spoofing | Replay stolen JWT at /login to impersonate user. | Bind tokens to device/TLS; short TTL; revocation list; MFA. | High | Medium |

| S-02 | API Gateway | Spoofing | Harvested API key used to call internal services as trusted client. | Vault-stored keys; regular rotation; enforce mutual TLS. | Low | |

| S-03 | Admin Portal | Spoofing | Phished admin credentials grant portal takeover. | Phishing-resistant MFA; brute-force guards; geofencing. | High | Medium |

| T-01 | Cart Submission | Tampering | In-flight JSON modified (e.g. price/quantity) to under-charge order. | Server-side total calculation; HMAC over payload; enforce HSTS+preload. | High | Medium |

| T-02 | Feature-Flag Service | Tampering | Unsigned flags tampered to enable global discount mode. | Sign & verify flag bundles; integrity checks in code. | Medium | Medium |

| T-03 | CI/CD Pipeline | Tampering | Malicious build inserted via compromised pipeline. | Signed artifacts; strict pipeline RBAC; SBOM verification. | High | Low |

| R-01 | Order DB | Repudiation | User disputes order; logs lack IP/jti linkage so origin unprovable. | Immutable WORM log; include IP, JWT_jti, timestamp per event. | Medium | Medium |

| R-02 | Payment Logs | Repudiation | Mismatch between internal and gateway logs denies payment proof. | Correlate via unique transaction IDs; synchronized timestamps; end-to-end logging. | Medium | Low |

| R-03 | Refund Process | Repudiation | Admin issues refund but later disputes having authorized it. | Dual approval; log admin ID and actions to tamper-proof store. | Medium | Low |

| I-01 | Error Handler | Info Disclosure | Stack traces leak internal hostnames, paths, and code. | Global exception handler; generic error codes; sanitized logs. | Medium | Low |

| I-02 | Logs → SIEM | Info Disclosure | PII (emails, addresses) forwarded unredacted to third-party SIEM. | Redact/tokenize sensitive fields before forwarding. | High | Medium |

| I-03 | Web App | Info Disclosure | Insecure Direct Object References allow access to other users’ data. | Enforce object-level auth checks; use unguessable IDs (UUIDs). | High | Medium |

| D-01 | /checkout Endpoint | Denial of Service | Layer-7 flood exhausts DB connections and payment gateway quotas. | Rate-limit per user/IP; circuit breakers; autoscale on queue latency. | High | Medium |

| D-02 | Auth Service | Denial of Service | Rapid login attempts lock out or degrade service. | CAPTCHA thresholds; progressive delays; IP throttling. | Medium | Medium |

| D-03 | Feature-Flag Service | Denial of Service | Third-party flag service outage breaks critical features. | Local flag cache; fallback defaults; timeouts and retries. | Medium | Low |

| E-01 | Web App / API | Elevation of Priv | Client-injected role field grants unauthorized admin privileges. | Strict JSON schema; strip unknown fields; server-side RBAC; cache invalidation on role changes. | High | Low |

| E-02 | Order Mgmt API | Elevation of Priv | Unpatched flaw exposes admin-only endpoints to low-privilege users. | RBAC enforcement at service layer; timely patching; WAF protections. | High | Low |

| E-03 | CI/CD Dashboard | Elevation of Priv | Low-privilege dev account escalates to pipeline admin via misconfigured IAM. | Principle of least privilege; IAM reviews; alert on privilege escalations. | High | Low |

| S-04 | Payment Gateway | Spoofing | Fake payment callback marks order as paid without real transaction. | Verify gateway signatures; mutual TLS; nonce in callback URLs. | High | Low |

| T-04 | Database Migration | Tampering | Migration script altered to drop or corrupt tables. | Code reviews for migrations; checksum validation; restricted migration roles. | High | Low |

| R-04 | Audit Archive | Repudiation | Archive job omits critical events, creating gaps in audit trail. | Monitor completeness; periodic integrity checks on archived logs. | Medium | Low |

| I-04 | CDN Cache | Info Disclosure | Sensitive API responses cached at CDN edge and exposed publicly. | Configure cache-control headers; segregate public/private content; require auth on origin fetch. | Medium | Medium |

| D-04 | Order DB | Denial of Service | Large batch jobs starve checkout transactions of DB resources. | Schedule off-peak; resource quotas; priority queues. | Medium | Medium |

| E-04 | Config Service | Elevation of Priv | Attacker modifies config to disable security controls or grant themselves rights. | Signed configs; change-approval workflows; audit trails. | High | Low |

| S-05 | Mobile App | Spoofing | Fake client binary issues API calls with stolen credentials. | App attestation; certificate pinning; anomaly detection. | Medium | Medium |

| T-05 | Cache Layer | Tampering | In-memory cache entries (e.g. price cache) corrupted via debug endpoints. | Secure debug interfaces; encrypt cache; integrity checks. | Medium | Low |

| R-05 | Third-Party Services | Repudiation | Third-party admins alter their logs, undermining non-repudiation of external events. | SLA-mandated WORM logging; periodic third-party attestation. | Low | Low |

Homework for you

I will give you two scenarios with Level 1 and Level 2 DFD diagrams and you have to now work on the above STRIDE lens and apply it strategically as a part of your homework exercise.

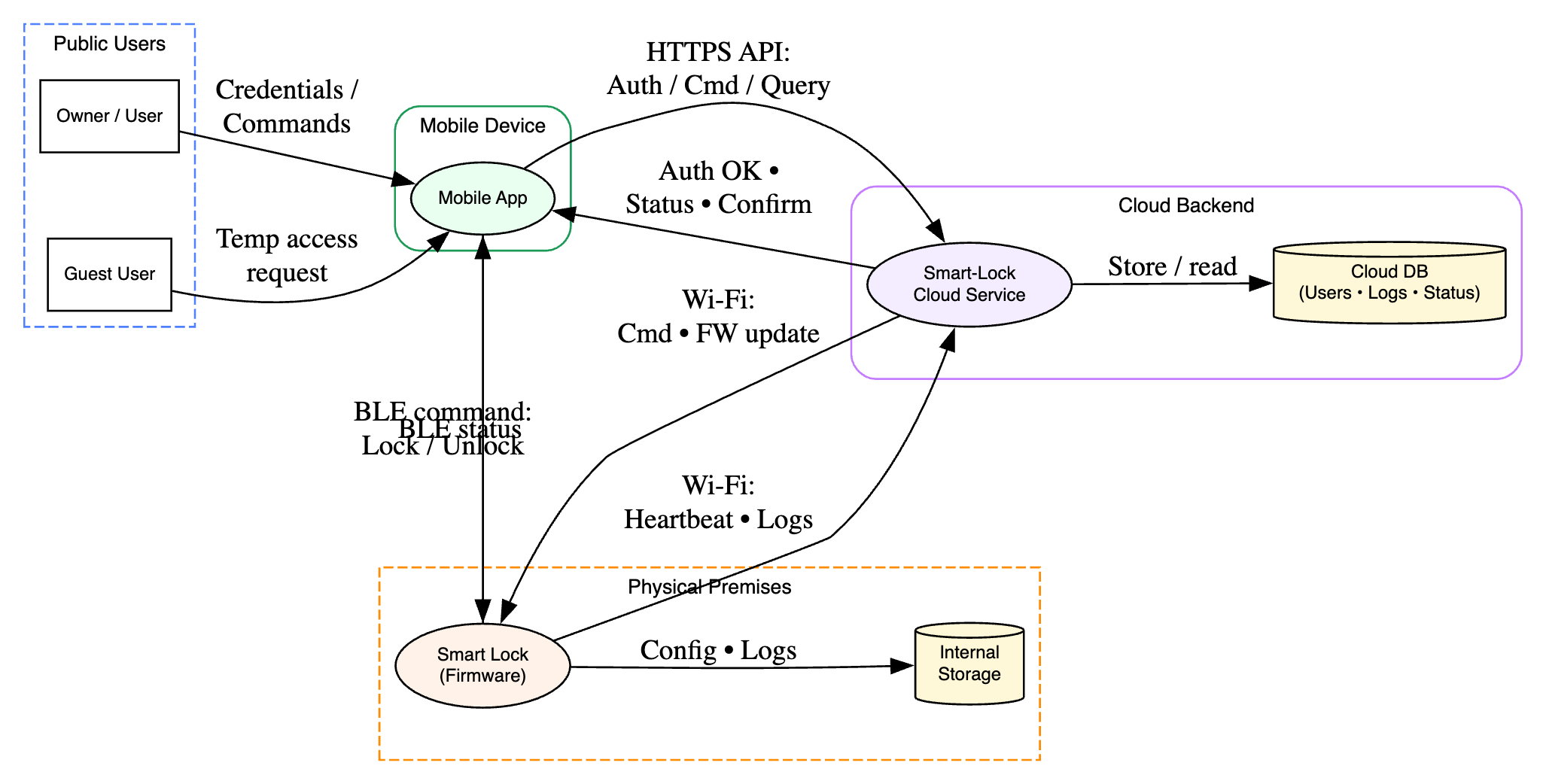

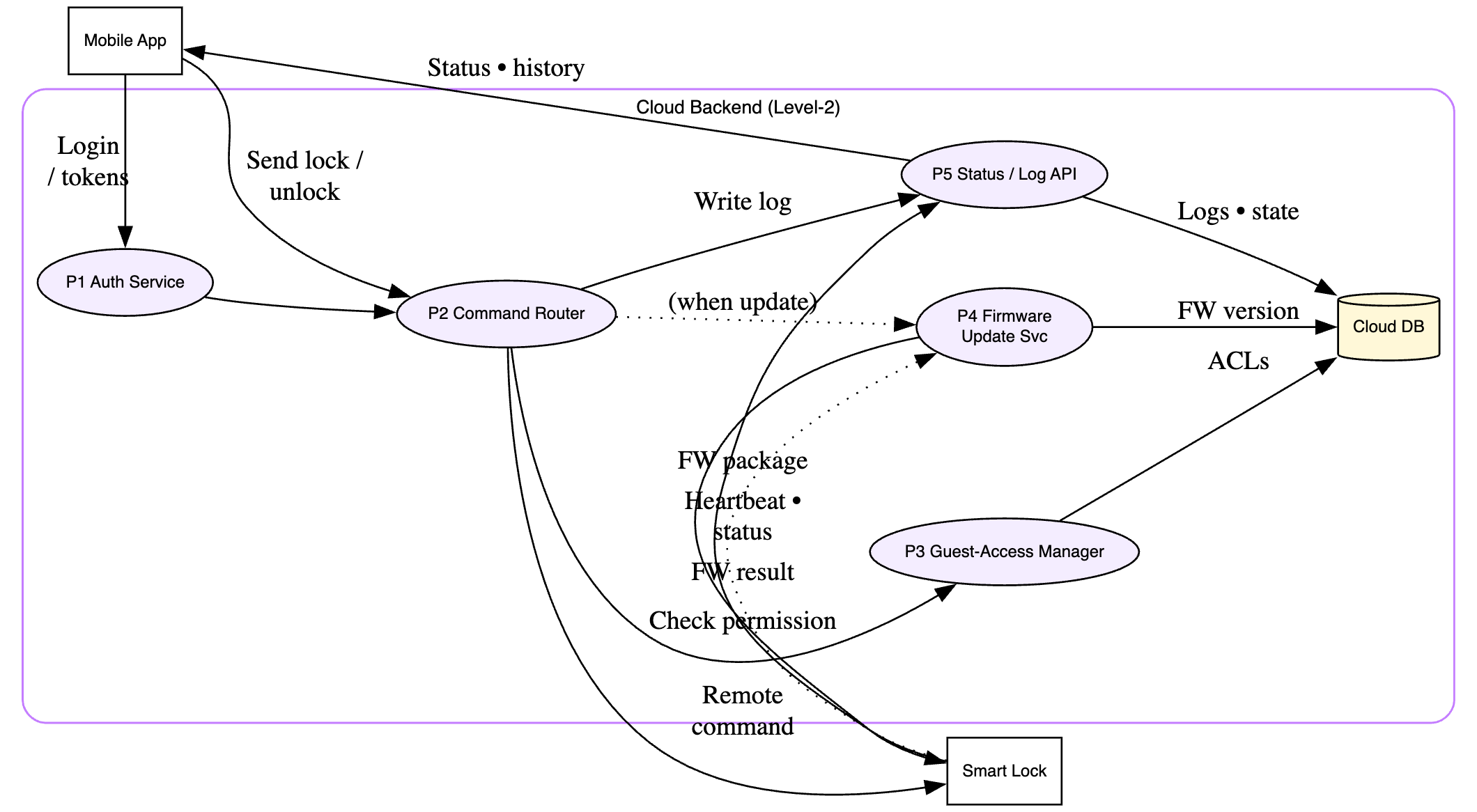

Scenario 2: Hardening an IoT Smart Lock System

Let’s shift gears from pure web APIs to the interconnected world of the Internet of Things (IoT). Consider a common smart home device: a Smart Lock. Users can lock/unlock their door using a mobile app, grant temporary access to guests, and check the lock’s status remotely.

System Overview

This system typically involves several components:

- The Smart Lock: The physical device on the door. Contains firmware, a microcontroller, communication modules (Bluetooth Low Energy - BLE, Wi-Fi), battery, and the locking mechanism.

- Mobile App: The user interface on a smartphone (iOS/Android). Used for control, configuration, and status viewing.

- Cloud Backend: Servers hosted in the cloud responsible for:

- User authentication and management.

- Storing lock status and history.

- Relaying commands between the app and the lock (especially when the user is remote).

- Managing guest access permissions.

- Communication Channels:

- App <-> Lock (often via BLE when nearby).

- App <-> Cloud (via HTTPS over Wi-Fi/cellular).

- Lock <-> Cloud (via Wi-Fi, often using protocols like MQTT or HTTPS).

Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs)

Level 1 DFD

Level 2 DFD

- External Entities: User, (potentially) Guest User.

- Processes: Mobile App, Cloud Backend, Smart Lock Firmware.

- Data Stores: Cloud Database (User accounts, Lock status, Logs, Guest permissions), Lock Internal Storage (Firmware, Configuration, maybe local logs).

- Data Flows:

- User -> Mobile App (Login credentials, Lock/Unlock commands)

- Mobile App -> Cloud Backend (Auth requests, Commands, Status queries)

- Cloud Backend -> Mobile App (Auth responses, Status updates, Confirmations)

- Mobile App -> Smart Lock (BLE commands - Lock/Unlock, Config)

- Smart Lock -> Mobile App (BLE status updates)

- Smart Lock -> Cloud Backend (Wi-Fi status updates, Heartbeats, Log uploads)

- Cloud Backend -> Smart Lock (Wi-Fi commands - Lock/Unlock, Firmware updates)

- Trust Boundaries: Between User & App, App & Cloud, Cloud & Lock, App & Lock (BLE), Physical boundary around the lock itself.

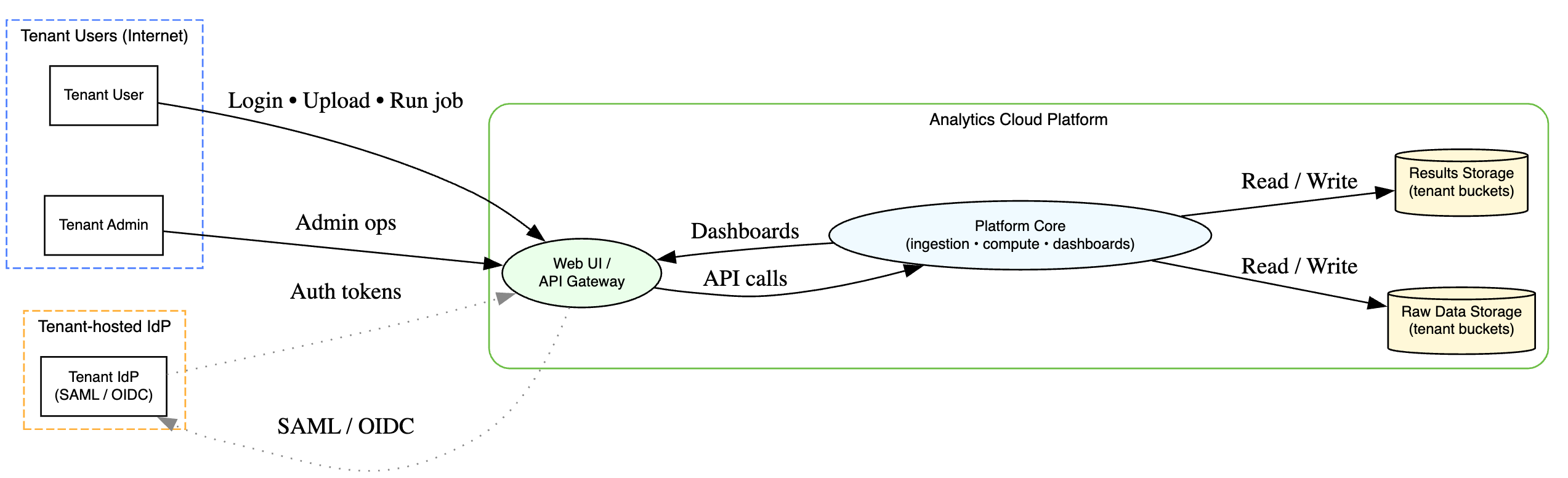

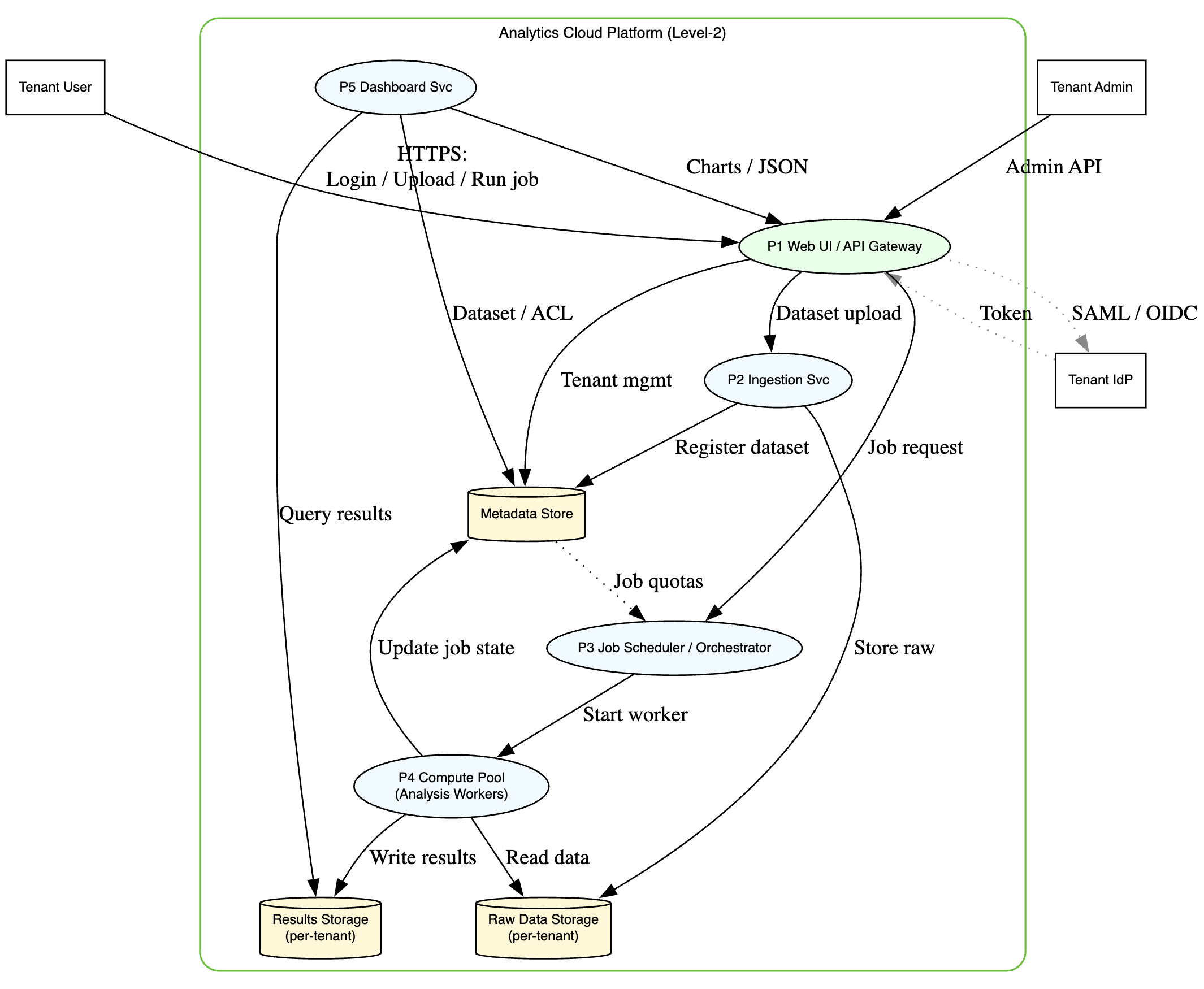

Scenario 3: Analyzing a Cloud-Based Data Analytics Platform

For our final scenario, let’s tackle something bigger and more complex: a multi-tenant, cloud-based data analytics platform. Think of a service where different companies (tenants) can upload their datasets, run complex analysis jobs, and visualize the results through dashboards.

System Overview

This platform likely involves numerous microservices running in a cloud environment (like AWS, Azure, or GCP).

- Web UI / API Gateway: The entry point for users. Handles authentication, serves the dashboard UI, and routes API requests for data upload, job management, etc.

- Ingestion Service: Receives uploaded data (potentially large files), validates it, perhaps performs initial processing/transformation, and stores it in tenant-specific storage.

- Data Storage: Cloud storage (like S3, Azure Blob Storage, GCS) partitioned by tenant to store raw and processed data.

- Compute/Analysis Service: Manages a pool of compute instances (VMs, containers) that run the actual analysis jobs defined by users. These jobs read data from storage and write results back.

- Job Scheduler/Orchestrator: Manages the queueing, scheduling, and execution of analysis jobs on the compute instances.

- Results Storage: Another partitioned storage area for analysis results.

- Dashboard Service: Queries results storage and presents data visualizations to users via the Web UI.

- Identity Provider (IdP): Handles user authentication, potentially integrating with tenants’ own IdPs (e.g., via SAML or OIDC).

- Metadata Store: Database holding information about tenants, users, datasets, jobs, permissions, etc.

Data Flow Diagrams (DFDs)

Level 1 DFD

Level 2 DFD

- External Entities: Tenant User, (potentially) Tenant Admin, Tenant IdP.

- Processes: Web UI/API Gateway, Ingestion Service, Compute Service (Job Execution), Job Scheduler, Dashboard Service, IdP.

- Data Stores: Raw Data Storage (Tenant-partitioned), Results Storage (Tenant-partitioned), Metadata Store, Compute Instance Ephemeral Storage.

- Data Flows: Numerous flows involving user interaction, data upload, job submission, data processing between storage and compute, result querying, authentication flows.

- Trust Boundaries: Between users and the platform, between tenants (CRITICAL!), between different internal microservices, between the platform and the underlying cloud provider APIs, between the platform and Tenant IdPs.

Making STRIDE Work for You: Practical Tips from the Trenches

Alright, we have seen STRIDE applied to a few different systems. But knowing the theory and making it work smoothly within a busy team are two different things. After 13 years wrestling with security in real-world projects, here are some practical tips – the stuff you learn by doing (and sometimes by messing up).

Getting started without getting overwhelmed:

- Start small, aim high: Don’t try to threat model your entire monolithic legacy system in one go. Pick a new feature, a critical component (like authentication or payment processing), or a specific user story. Get a win, learn the process, and then expand.

- Focus on the flows: Data Flow Diagrams are your friends. Even a simple whiteboard DFD focusing on the main data movements and trust boundaries is incredibly valuable. Don’t get bogged down in perfecting the diagram initially; focus on understanding the system.

- It’s not about perfection (at first): Your first threat model won’t be perfect. You will miss things. That’s okay. The goal is to get better at identifying risks proactively, not to achieve theoretical perfection on day one.

Common Pitfalls to Sidestep:

- Boiling the ocean: Trying to model too much at once. Scope is crucial. Define clear boundaries for your analysis.

- Analysis paralysis: Spending endless hours debating the exact risk rating or the perfect DFD symbol. Get the main threats identified and documented; refinement can come later.

- DFD extremes: Diagrams that are either so high-level they’re useless or so detailed they’re unreadable. Find the right level of abstraction for the component you are modeling.

- Forgetting trust boundaries: These are critical! Pay extra attention to anywhere data or control crosses from a less trusted zone to a more trusted one (or vice-versa).

- The checkbox mentality: Threat modeling isn’t a one-time task you do just to satisfy compliance. It’s a continuous way of thinking. Revisit models when designs change significantly.

Integrating into DevSecOps (Making it stick):

- Shift Left, seriously: The earlier you threat model, the better. Discuss potential threats during design reviews or even backlog grooming for complex features.

- Threat Model per feature/story: For significant changes, make a lightweight threat model part of the definition of done. What new threats does this introduce? How are we mitigating them?

- Link to other tools: Findings from SAST (Static Analysis Security Testing) or DAST (Dynamic Analysis Security Testing) can feed into your threat model, and your threat model can help prioritize SAST/DAST findings. Is that injection vulnerability targeting a critical data flow identified in your model?

- Automate where sensible: While the core thinking requires humans, tooling can help. Generating DFDs from code (with limitations), using dedicated threat modeling tools, or integrating threat lists into ticketing systems can streamline the process.

A Word on Tooling:

Yes, there are tools in the market! OWASP also has resources, and other commercial tools exist. But remember: the tool supports the process, it doesn’t replace the thinking. A fancy tool won’t help if you don’t understand the system or the STRIDE categories.

Summary – The People Part

Honestly, the biggest challenge often isn’t technical; it’s cultural. Threat modeling works best when it’s a collaborative effort. Get developers, testers, architects, and security folks in a room (virtual or physical). Developers know the code inside out, testers know how things break, architects see the big picture, and security brings the threat landscape perspective.

Don’t let it become a security team throwing findings over the wall. Make it a shared responsibility, a learning opportunity for everyone involved. When developers understand the why behind a security requirement, they’re much more likely to implement it effectively. Foster a culture where asking “What could go wrong here?” is a normal part of building software.

Ultimately, STRIDE is a means to an end: building more secure, resilient systems. It provides structure and helps ensure you are not missing entire categories of threats. Use it pragmatically, adapt it to your team’s workflow, and focus on the collaborative process of identifying and mitigating real risks.

So, the next time you are designing a new feature or system, give it a try. Sketch out a quick DFD, run through the STRIDE categories, and see what you uncover. You might be surprised at how this simple framework can help you build more robust and resilient software. Keep learning, keep questioning, and stride on!